CT Head wo

Normal

BRAIN:

No acute loss of grey-white differentiation.

No bleed.

No mass effect.

CSF:

No midline shift of the interventricular septum.

Ventricles normal in size.

Basal cisterns patent.

SINUSES:

No air-fluid level.

BONES:

No mastoid effusion.

No acute fracture or dislocation.

No suspicious osseous lesions.

ORBITS:

Globes intact.

Lenses anatomically aligned.

Normal intraorbital fat.

No intraconal, extraconal, or subperiosteal abscess, hematoma, or mass.

SOFT TISSUE:

No scalp hematoma.

Reporting Infarcts

Cerebral or cerebellar hemisphere

When you see an infarct, use this form:

(Acute/chronic) (right/left) (location) infarct, (vessel) territorywhere:

location =

{

frontal/parietal/occipital/temporal) lobe,

cerebellar,

}and

vessel =

{

MCA,

ACA,

PCA,

SCA,

AICA,

PICA

}Examples:

Acute right frontal and parietal infarct, MCA territory.

Chronic left cerebellar infarct, SCA territory.

Basal ganglia and brainstem

When you see a small discrete CSF-density hole in the basal ganglia or brainstem, use the term "chronic lacunar infarct". Omit the vascular territory.

Chronic lacunar infarct left caudate.If these areas are hypodense but denser than CSF, with less defined contours, you may be looking at an acute infarct. Use this language:

Acute infarct left pons.Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy

Severe loss of oxygen and blood flow, such as from strangulation or prolonged asystole, causes diffuse brain infarction and swelling. The arteries and dural venous sinuses may look like subdural bleed - don't be fooled. You'll report the Brain and CSF sections as follows:

BRAIN

Diffuse loss of gray-white differentiation.

No bleed.

Diffuse sulcal effacement.

CSF:

No midline shift of the interventricular septum.

Ventricles narrowed.

Basal cisterns effaced.Hemorrhagic transformation

Acute infarcts are at risk for bleeding roughly 2-7 days after onset. Use this phrase immediately after describing the acute infarct location.

Hemorrhagic transformation.Bleeding

The terms bleed, hematoma, and hemorrhage are used interchangeably in reports, although they convey subtle differences in meaning. We'll selectively use the term "bleed" since it's shorter to type, and doesn't carry any subtext about whether the bleed is organized (hematoma), or large in volume (hemorrhage).

Types of bleed

Here are the types of bleed you'll need to report:

- Epidural bleed- look along the inner table near skull fractures

- Subdural bleed - look along the inner table, falx, and tentorium

- Subarachnoid bleed - look in the sulci and basal cisterns, including the Sylvian cisterns. Can be traumatic (eg. head hits floor) or atraumatic (eg. aneurysm rupture).

- Intraventricular bleed - look in the occipital horns for trace intraventricular bleed. Casting is when a large intraventricular bleed mostly or completely fills one or more ventricles.

- Intraparenchymal bleed - look within the brain tissue; middle crania fossa is a classic blind spot. Contusion = intraparenchymal bleed from blunt-force trauma to the skull; like a bruise in the brain. Hypertensive hemorrhage is intraparenchymal bleed from severe hypertension.

Extra-axial bleeds

Small bleeds where epidural versus subdural is ambiguous. Report as follows:

(Right/left) (frontal/parietal/temporal/occipital) acute extra-axial bleed.Epidural bleeds

associated with an overlying skull fracture.

(Right/left) (frontal/parietal/temporal/occipital) acute epidural bleed.Subdural bleeds

cross suture lines, and tend to be less discrete and lentiform than epidural hematomas. You'll need to communicate if the subdural hematoma is hyperacute, acute, subacute, or chronic, depending on density.

- hyperacute - gradient of low density anteriorly, and higher density in the posterior dependent portions where the red blood cells are sedimenting.

- acute - hyperdense relative to brain

- subacute - isodense relative to brain

- chronic - hypodense relative to brain

- mixed-age - various densities

Here's how to report a subdural bleed:

(Right/left/bilateral) (convexity/frontal/parietal/temporal/occipital/tentorial) (mixed-density/mixed-density acute/hyperacute/acute/subacute/chronic) subdural bleed.Use the term mixed-density acute to communicate the combined presence of acute components with subacute subacute and/or chronic components. In the hospital, you'll more commonly see the phrase acute-on-chronic subdural hematoma, which commonly lumps together subacute and chronic hematomas with acute components. This level of imprecision still works, because the relevant message for patient care is that an acute event has occurred, and this is a recurring problem, whether the previous event was subacute or chronic.

Use the term convexity when the bleed spans the frontal and parietal bones. Use the term bifrontal if the bleed spans the bilateral frontal lobe.

Here's how to report the subdural bleed if it's located adjacent to the falx:

(Anterior/posterior) (right/left) parafalcine acute subdural bleed.If the bleed is along both sides of the falx, use this:

(Anterior/posterior) parafalcine acute subdural bleed.If the bleed is along both sides of the falx, and along both anterior and posterior parts, use this:

Parafalcine acute subdural bleed.Notice we don't bother with acute/subacute/chronic here, because typically only the acute bleeds are readily apparent in this location.

Subdural empyemas are pus-filled collections (abscesses) that will look isodense to hypodense relative to brain parenchyma—similar to subacute subdural hematomas—and may be associated with an intra-parenchymal abscess. Use the same basic format to report subdural empyemas:

(Blank/right/left/bifrontal) (convexity/frontal/parietal/temporal/occipital/parafalcine/juxtatentorial) subdural empyema.Subarachnoid bleed

can be related to trauma (traumatic subarachnoid bleed) or atraumatic (typically related to aneurysm rupture). It is most apparent when it is acute. The distribution of the subarachnoid bleed relates to the direction of traumatic force, or to the location of aneurysm rupture. Although we'll use the term subarachnoid bleed, you'll also hear the synonymous term subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

Here's how to report an acute subarachnoid bleed that's primarily located in the cerebral hemispheres (typically traumatic etiology):

(Right/left/bilateral) (frontal/parietal/temporal/occipital) acute subarachnoid bleed.Here's how to report an acute subarachnoid bleed that involves a portion of the basal cisterns (typically atraumatic, related to aneurysm rupture):

Acute subarachnoid bleed predominantly centered on the (blank/right/left/bilateral (interpeduncular/crural/ambient/quadrigeminal) cistern.If the acute subarachnoid bleed fills the basal cisterns without a particular emphasis, write this:

Acute subarachnoid bleed filling the basal cisterns.If the acute subarachnoid bleed fills the cerebral hemispheres and basal cisterns, write this:

Acute subarachnoid bleed involving the (-/left-greater-than-right/righ-greater-than-left) cerebral hemispheres and basal cisterns.If both sides are equally involved, skip the modifier, indicated with the "-".

Intraventricular bleed

describes blood in the ventricles.

Small intraventricular bleed will pool in the occipital horn.

Acute intraventricular bleed, occipital horn of (bilateral/right/left) lateral ventricle.For larger intraventricular bleed, you can alternatively describe the location of the blood:

Acute intraventricular bleed, (right/left/bilateral) (frontal horn/body/atrium/occipital horn/temporal horn/third ventricle, fourth ventricle).Casting is complete filling of a ventricle with blood, used to communicate the severity and large volume of bleed.

Acute intraventricular bleed, with casting of the (right/left) lateral ventricle.Intraparenchymal bleed

describes blood in the brain tissue. Use this phrase:

Acute intraparenchymal bleed, (list of locations).For items in the list of locations, indicate the side (right/left/bilateral), followed by the general location

- (frontal/parietal/temporal/occipital) lobe

- cerebellar hemisphere, cerebellar vermis

- caudate/lentiform nucleus/putamen/thalamus

For example, "Acute intraparenchymal bleed, left frontal lobe, right occipital lobe, right lentiform nucleus."

Don't use more specific words to speculate on the cause for the intraparenchymal bleed in your preliminary report, but here are some of the more common causes that you might see referenced in a final report from the radiologist:

- blunt-force trauma (contusion)

- severe hypertension (hypertensive hemorrhage)

- hemorrhagic mass

- vascular malformation

- low platelets (petechial hemorrhage)

- anticoagulation

Squished Brain

When bleed, mass, or CSF takes up more space in the skull, the brain gets squished. We call that mass effect. Here are some variations of mass effect to include in your preliminary report.

Mass that's not hematoma

When the mass effect is caused by a mass that is not hematoma, you'll want to describe the mass. Without an MRI, it's hard to know exactly what the mass is - metastatic disease, primary brain tumor, meningioma, abscess, tumefactive demylenation, or any other mass. So you'll use this simple phrase instead:

(Left/right/midline) <location> <density> mass

location = {frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, cerebellar, tectal, midbrain, pontine}

density = {(hypodense, isodense, hyperdense}Examples)

Right frontal hyperdense mass.

Left cerebellar hypodense mass.

Multiple hypodense masses in the bilateral frontal and parietal lobes, and left cerebellar hemisphere.

The patient will need an MRI Brain with and without contrast to further characterize the mass, but at least you've identified the mass for now.

Midline shift

When mass effect pushes the brain aside, the interventricular septum gets displaced:

[X]mm (left-to-right/right-to-left) midline shift of the interventricular septum.where X is the number of millimeters of shift, drawing a perpendicular line from the interventricular septum to the mid-sagittal line. You can draw the mid-sagittal line by connecting the anterior and posterior insertions of the falx. If the interventricular septum is to the right of midline, use the phrase left-to-right midline shift. If the interventricular septum is to the left of midline, use the phrase right-to-left midline shift.

Sulcal narrowing

If the mass effect only narrows the immediately-adjacent sulci, use:

Local mass effect.Here's an example with epidural bleed:

Acute right frontal epidural bleed. Local mass effect.

If the mass effect involves the entire right or left cerebral hemisphere, use:

Sulcal narrowing, (left/right) cerebral hemisphere.Here's an example with mass:

Hypodense mass, right frontal lobe. Sulcal narrowing, right cerebral hemisphere.

With cerebral edema, sulci can become symmetrically narrowed everywhere,

Diffuse sulcal narrowing.or the sulci are diffusely completely closed:

Diffuse sulcal effacement.In young patients (<20 yo), it's easy to miss the life-threatening diagnosis of diffuse sulcal effacement, because the finding is symmetric, and younger patients normally will have narrower sulci. But look at the vertex—even young patients should have some space at the vertex.

In older patients (70+yo), raise the possibility of cerebral edema even if the sulci are narrowed but not effaced. Normal older brains have wider sulci than younger brains, because of age-related volume loss. You'll need to get a sense for what's normal for older brains to make this judgement call.

If you've raised the possibility of diffuse cerebral edema, look to the crural cisterns to check for uncal herniation, and the foramen magnum to check for cerebellar tonsillar herniation.

Squished CSF

Narrowed ventricles

Sometimes ventricles are narrowed, and it's usually the lateral ventricles that are most immediately noticeable. Use the term effacement to mean completely squished.

(Narrowing/effacement)When the lateral ventricles are symmetrically narrowed by cerebral edema, use simple language to describe that.

(Narrowing/effacement) of the lateral ventricles.When the narrowing is unilateral, usually due to a mass, say this instead.

(Narrowing/effacement) of the (left/right) lateral ventricle.Sometimes the mass effect is so great that it pinches off the third ventricle and/or contralateral foramen of Monro, causing CSF to build up in the contralateral lateral ventricle. This is called entrapment, and you'll write about it like this:

(Narrowing/effacement) of the left lateral ventricle and enlargement of the right lateral ventricle representing entrapment.mass effect on the left, with entrapment on the right

or like this:

(Narrowing/effacement) of the right lateral ventricle and enlargement of the left lateral ventricle representing entrapment.mass effect on the right, with entrapment on the left

The other ventricles (third, fourth) might be narrowed as well, but often omitted. If the mass effect is centered on the cerebellum, like a cerebellar primary tumor or metastasis, you might see:

Effacement of the fourth ventricle, with enlargement of the third and lateral ventricles, representing obstructive hydrocephalus.posterior fossa mass, effacing 4th ventricle, w/ enlargement of 3rd and lateral ventricles

Narrowed basal cisterns

Some or all of the basal cisterns may be narrowed, including the quadrigeminal plate cistern (alternatively called the quadrigeminal cistern), ambient cisterns, crural cisterns, interpeduncular cistern, suprasellar cistern, Sylvian cisterns, and cisterna magna. In this case, write:

Basal cisterns narrowed.In a more severe situation, the basal cisterns are completely closed. In that case, use this language:

Basal cisterns effaced.If you see brain tissue from the medial temporal lobe squeezing against the midbrain, add this note:

(Left/right) uncal herniation.If the cisterna magna is narrowed by the cerebellar tonsils, particularly with the cerebellar tonsils more than 5 mm below the foramen magnum on sagittal, be sure to add:

Cerebellar tonsillar herniation.Enlarged Ventricles

Uncertain etiology. Sometimes the ventricles are symmetrically enlarged, but we don't know exactly why. Report this as follows:

Ventricles (mildy/moderately/severely) enlarged.This statement is sufficient for a preliminary report, and does not commit you to identifying why the ventricles are symmetrically enlarged. There are four common reasons for symmetric enlargement, and you can optionally modify the dictation to reflect that if you are confident in the underlying diagnosis, because it guides treatment.

Volume loss. Brain atrophy with age is proportionate to ventricular size. You may write this as:

Ventricles (mildy/moderately/severely) enlarged, representing ex vacuo dilatation.Normal pressure hydrocephalus or central pattern of volume loss. These are two different diagnoses that are hard or impossible to differentiate on head CT. Central pattern of volume loss means that the periventricular white matter has more selectively atrophied versus the surrounding cortex, keeping the cerebral sulci from looking widened, but allowing for ex vacuo dilation of the ventricles. You may see this written as follows:

Ventricles (mildy/moderately/severely) enlarged, out of proportion to level of volume loss, which may represent normal pressure hydrocephalus versus central pattern of volume loss.Obstructive hydrocephalus. A mass narrows the third ventricle, causing the lateral ventricles to balloon. Alternatively, a mass narrows the fourth ventricle, causing the third and lateral ventricles to balloon. Express that as follows:

(Lateral/third) ventricles (mildy/moderately/severely) enlarged, obstructive hydrocephalus.Bones

Mastoid Effusion

Mastoid effusion is fluid in the mastoid portion of the temporal bone. Mastoid effusion can occur due to a temporal bone fracture, mastoiditis, or other causes. Describe a mastoid effusion as follows:

(Right/left) mastoid effusion.In final radiology reports, you will see the mastoid effusion graded qualitatively as mild, moderate, or severe. But don't include those modifiers in your preliminary report.

Sinuses

In trauma, air-fluid levels in the sinuses are markers of sinus wall fractures. In non-trauma cases, they are markers of acute sinusitis. Describe them like this:

Air-fluid level, (right/left/bilateral) (maxillary/frontal/ethmoid/sphenoid) sinus.When air-fluid levels involve all of the sinuses, use this:

Pansinus air-fluid levels.You'll see this with major facial trauma.

Fractures

Describe the location of the fracture, and whether the fracture is acute, chronic or unknown age. Whether to contemplate the age of the fracture, and whether to use the term deformity, varies across fracture locations, so we've included that information below.

The term comminuted means there are multiple parts to the fracture. We've indicated the common bones where people mention comminuted. With the other locations, bones fractures might be more commonly comminuted, and it may not be informative to add that modifier. Use the phrases below as guidance.

Basic skull fracture, excluding temporal bone:

Acute (comminuted) (non-displaced/depressed) (left/right) (frontal/parietal/occipital) bone fracture.Basic skull fracture, temporal bone:

Acute (comminuted) (left/right) temporal bone fracture, (sparing/involving) the otic capsule.Zygomatic arch fracture:

(Acute/chronic/unknown age) (comminuted) (left/right) zygomatic arch fracture.Lamina papyracea fracture:

Acute (left/right) lamina papyracea fracture.

Chronic (left/right) lamina papyracea fracture deformity.The lamina papyracea is the part of the medial orbital wall that covers the ethmoid sinus, and it's part of the ethmoid bone.

Orbital wall fracture:

Acute (left/right) (superior/inferior/medial/lateral) orbital wall fracture.For isolated involvement of the lamina papyracea, use the lamina papyracea phrase instead of the orbital wall phrase.

Nasal bone fracture:

Acute (left/right/bilateral) nasal bone fracture.

Unknown age (left/right/bilateral)nasal bone fracture.

Chronic (left/right/bilateral)nasal bone fracture deformity.Maxillary sinus wall fracture:

Acute (left/right) maxillary sinus fracture involving the (anterior/posterior/medial/inferior) wall.Frontal sinus wall fracture:

Acute (comminuted) (depressed) (left/right) frontal sinus wall fracture involving the (inner table/outer table/inner and outer table).Just as you would for skull fractures elsewhere, use the modifier depressed for the frontal sinus wall fracture if the inner table is displaced towards the brain. Note that the frontal sinus wall is actually just a part of the frontal bone. You might see anterior/posterior wall used in the hospital instead of inner/outer table, depending on radiologist preference.

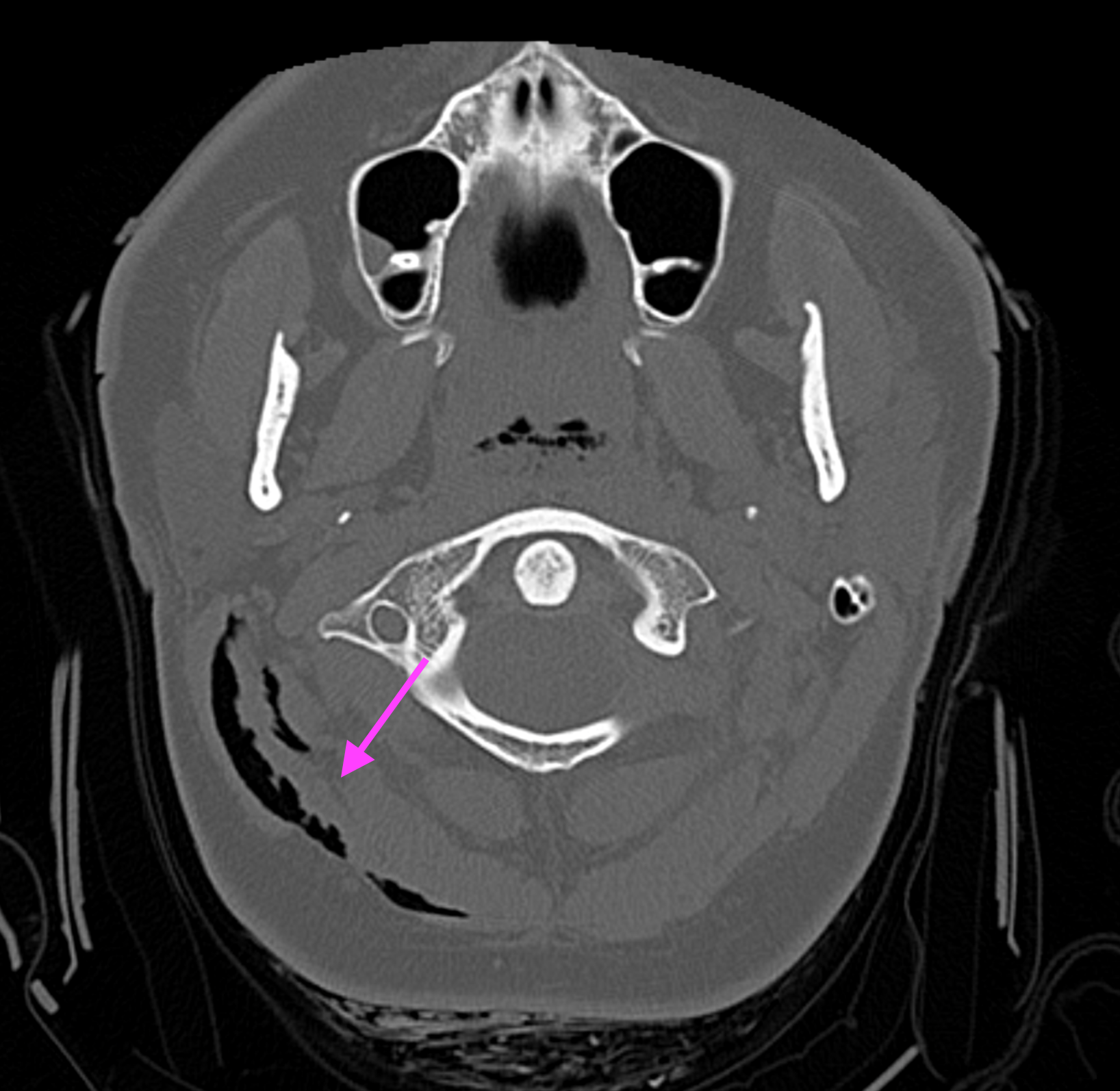

Because the tiniest amount of the cervical spine peaks into the CT head, you're responsible for catching fractures in that area too.

Here's how you report a C1 fracture:

Acute fracture (anterior/posterior) C1 arch (with/without) extension to (right/left/bilateral) transverse foramen.Here's how you report a dens (C2) fracture:

Acute dens fracture.Globe Abnormalities

If the patient has linear-appearing lenses instead of the normal lentiform appearance of the lenses, use this phrase:

Bilateral lens replacements.If the globes are shifted anteriorly in the orbits relative to the interzygomatic line, use this phrase:

(Right/left/bilateral) proptosis.If trauma has destroyed the contour of the globe, write:

(Right/left) globe rupture.Soft Tissue

Soft tissues you might report include the scalp and premalar area, which is the cheek in front of the maxillary sinus. The level between the eyes and the C1 arch also contains many additional soft tissue spaces, which radiologists call the "head and neck", which you won't need to worry about unless you're going into neurosurgery, ENT or radiology.

Scalp swelling

Scalp swelling manifests as diffuse thickening of the scalp with similar or lower density than the adjacent scalp on soft tissue window, reflecting edema (water).

(Right/left) (frontal/parietal/temporal/occipital/convexity) scalp swelling.Scalp hematoma

Blood collecting in the scalp takes a lentiform shape, and has higher density than the surrounding scalp on soft tissue window.

(Right/left) (frontal/parietal/temporal/occipital/convexity) scalp hematoma.Use the term "convexity" if the hematoma bridges the frontal and parietal regions.

Scalp laceration

Look for irregularity of the skin, or air dissecting into the soft tissue.

(Right/left) (frontal/parietal/temporal/occipital) scalp laceration.See Also

Head CT Search Pattern by RadClerk